Despotism, neoliberalism and climate change: Morocco's catastrophic convergence

By Jawad Moustakbal

Claims of Morocco's exceptionalism during the Arab Spring now ring hollow as protests spread in the face of elite policies that deny dignity to the majority

Claims of Morocco's exceptionalism during the Arab Spring now ring hollow as protests spread in the face of elite policies that deny dignity to the majority

On Friday, 28 October 2016, a tragic fatal incident happened in Al Hoceima city in northeastern Morocco when a state official seized wares from Mohsin Fikri, a fish vendor, and had it thrown into a garbage truck. When the vendor desperately climbed into the truck to reclaim his fish, “a local police officer ordered the garbage truck driver to start the compactor and 'grind him," according to activists and witnesses. The truck horrifically ground up Fikri, killing him.

'We were only at the beginning of a long-term revolutionary process that will go on for years and decades'

- Gilbert Achar, School of Oriental and African Studies

This tragedy and the protests that followed were reminiscent of the wave of demonstrations that Morocco witnessed with the onset of the 20th February Movement in 2011 during the so-called Arab Spring. They provided an impetus for Moroccans to continue their fight for dignity, freedom and social justice and have shown that the process of real transformation in Morocco – and more broadly across North Africa and West Asia – is not finished yet.

Rather, the desire for change has been thwarted by rulers and elites since it began. These elites wanted that “spring” to be a passing one which quickly turned to autumn, dashing the hopes of everyone who took to the streets calling for their inalienable right for dignity and freedom.

“We were only at the beginning of a long-term revolutionary process that will go on for years and decades,” Gilbert Achar, professor of development studies and international relations at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), said last year. “As in every such historical process, there will be ups and downs, revolutions and counter-revolutions, upsurges and backlashes.”

Mourners carry the coffin of Fikri in the northern town of Hoceima on 30 October (Reuters)

With the connivance of most of the political and intellectual elite, the rulers hastened to promote the country was ranked to the rule. Nonetheless, this claim of stability has been contradicted by these recent incidents and the rapid and major mobilisation that took place in more than 40 cities in Morocco in recent months.

This mass mobilisation brought activists into the streets, voicing their rejection of contempt and humiliation collectively referred to in Morocco as hogra and to stand in solidarity with the oppressed. Actions such as this attest to the latent power of the masses which will undoubtedly undo the forces of oppression and colonialism which have been crushing our free will since our so-called independence in 1956.

Two Moroccos

Any follower of the general scene in Morocco is dazzled by the stark contradictions of a tale of two Moroccos. On the one hand, a Morocco of mega projects: Tanger-Med Port, highways, high-speed trains (on the Train à Grande Vitesse, “high-speed train” TGV model), luxurious cars, villas, palaces and touristic resorts with large pools and vast golf courses.

In contrast, one finds a Morocco which ranks very low in the human development index (HDI), vacillating between 126 and 130 out of 188 countries during recent years. As of 2013, the country was ranked 15th on the index in the Arab world and fourth in the Maghreb region behind Libya, Algeria and Tunisia.

Any follower of the general scene in Morocco is dazzled by the stark contradictions of a tale of two Moroccos

In this Morocco, 15 percent of the population lives in poverty and, according to a 2014 survey conducted by the High Commission for Planning, children attend school for an average of 4.3 years compared to a world average of 7.7 years. Here, there are reports of women who have been forced to give birth on the street outside of hospitals because staff denied them access. Many others are simply deprived of health services.

Moreover, since the adoption of the International Monetary Fund’s structural adjustment programme in the early 1980s, Morocco gave up its food sovereignty and became vulnerable to price fluctuations of staple goods on the global market. We have to import increasing amounts of wheat to meet our needs.

Moroccan farmers sows fertiliser over a wheat field in Rabat (AFP)

Moroccan farmers sows fertiliser over a wheat field in Rabat (AFP)

Morocco has also placed the fate of its energy in the hands of international and local private companies whose main interest is the insatiable accumulation of profits at the expense of Moroccans who are forced to pay exorbitant electricity bills which just keep rising.

In his book Tropic of Chaos: Climate Change and the New Geography of Violence, American author, journalist and professor Christian Parenti elaborates on the concept of catastrophic convergence – by which he means the convergence of militarism, neoliberalism and climate change - which he argues has devastated numerous regions worldwide. As is the case for many countries in our region, the stark contradictions and injustice we are experiencing in these two Moroccos are well-explained by Parenti’s concept.

Specifically, we are seeing the coming together of political despotism as the makhzen – the patronage network of royals, military officials, landowners, civil servants and others around the king - has taken over almost all political and economic decisions in the country; economic neoliberalism with the dominating forces of neo-colonialism, privatisation and export-oriented development; and finally climate change, especially extreme events like droughts and floods.

The crushing machine of political despotism

During the second half of the 1990s, Morocco witnessed a slight improvement in political freedoms as a part of preparations for the transition of power from King Hassan II to his son King Mohamed VI, and also in the context of the “new world order” as US President George HW Bush coined the era following the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War between the US and Russia.

In reality, however, the main factor that contributed to these gains in political freedoms was the perseverance and sacrifice of generations of tireless Moroccan citizens and activists who had not spared any effort to fight heart and soul against a machine of repression and intimidation imposed by the dictatorship of Hassan II since the 1960s.

The relative improvement could not hide the persistent forms of political despotism baptised “the new concept of authority”. Moreover, certain state practices from the old era continued including kidnappings, investigations under torture and unjust charges, especially after the terrible suicide terrorist attacks in Casablanca on 16 May 2003.

The 20 February Movement in Morocco and, more broadly, the extraordinary uprisings led by the region’s youth after the death of the Tunisian street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi in December 2010 marked a historic turning point that forced the authoritarian regimes to make some concessions, some of which, in hindsight, were purely tactical and mainly aimed at neutralising popular anger.

Members of the 20 February Movement carry flares during a demonstration on 6 November 2016 in Rabat (AFP)

Members of the 20 February Movement carry flares during a demonstration on 6 November 2016 in Rabat (AFP)

In Morocco, the success of this tactic manifested itself in the weakening and then apparent demise of the 20 February Movement in early 2012, as many activists faced a systematic backlash from the state, including false accusations, trials based on flimsy evidence, imprisonment, and being fired from their jobs. For instance, Moad, a young rapper, also known as El-Haqed, or “the Enraged”, who was considered to be the voice of the movement, has been arrested and jailed many times since 2012.

READ MORE ►

Inside the movement: what's left of the 20 February?

It is noteworthy that the backlash faced by men and women protesting the regime is merely a small fraction of the wider backlash of the state against citizens following the demise of the 20 February Movement. Illegal houses – the same ones that officials ignored as they were constructed in poor neighbourhoods in several parts of the country - were demolished.

The machine of political despotism resumed its activities by suppressing all forms of protests organised by diverse segments of society, including trainee teachers, medical students, workers at Maghreb Steel, the tribes of the Guich Loudaya and the Ouled Sbita who were defending their rights for decent housing against greedy real estate developers.

'Are you a government or a gang?'

In 1955, Mohammed Abdelkrim al-Khattabi – a leader in the Rif region where Mohsin Fikri was killed - addressed the first government appointed by late King Mohammed V and headed by Mbareq El Bekkay Lehbil. “Are you a government or a gang?” he asked.

Al-Khattabi’s now infamous saying rings true for the current situation in Morocco as our rulers put the people at an impasse of an impossible choice: servility and submission in the face of the annihilation of what remains of our social gains, or chaos, using the bogeyman of the ongoing Syrian genocide under the leadership and complicity of Western states and the war against the Yemeni people led by Saudi Arabia as examples.

Our rulers put the people at an impasse of an impossible choice: servility and submission in the face of the annihilation of what remains of our social gains, or chaos, using the bogeyman of the ongoing Syrian genocide or Yemen war

The dramatic death of Mohsin Fikri at the end of last October as a result of a corrupted and oppressive system is proof that the crushing political despotism machine has not been broken yet, and the task of uprooting it remains on our shoulders. However, the ongoing protests in the country’s northern cities also show that the spirit of Abdelkrim al-Khattabi, a symbol of struggle against all forms of colonialism and dependence, still haunts Morocco’s rulers.

With the help of political repression, in place since the fake independence of the country in 1956, and the Makhzen’s monopoly on political decision making, Morocco’s ruling classes have imposed liberal economic choices on the country. The pace of these choices increased with the implementation of the structural adjustment programme in the early 1980s, the adoption of the privatisation law in 1989 and the establishment of the ministry of economy and privatisation.

A 1948 photo of Abdelkrim al-Khattabi (L), with his brother, leader of the rebellion in the Rif (AFP)

A 1948 photo of Abdelkrim al-Khattabi (L), with his brother, leader of the rebellion in the Rif (AFP)

Some of the main economic choices which international financial institutions, in particular the World Bank and the IMF, dictated included abandoning public services such as education and health, privatising public facilities and institutions, shifting towards an export-oriented economy, particularly in agriculture, opening up of Moroccan market to foreign products, and decreasing subsidies for basic products like wheat, sugar and oil - and even cancelling the petrol subsidy. These economic trends were deepened by ostensibly “free” trade agreements signed by Morocco in the mid-1990s.

Over 35 years following the diligent implementation of these neoliberal strategies, one can assert that they failed miserably to achieve their stated goals, chief among them controlling macroeconomic indexes and achieving high economic growth rates. On the contrary, these trends had a catastrophic social impact, exacerbated our economic dependency on debt, international institutions and former colonisers and dealt a blow to what remained of our national sovereignty.

Energy piracy

The fuel sector is a stark example of the sheer failure of those policies. A current example is the closure of La Samir, the only refinery in Morocco, and the displacement of workers and their families after it was left bankrupt.

Meanwhile, those who benefited from its privatisation transferred their profits abroad, incurring a loss to the state of nearly $5bn. The liberalisation of the oil prices, which was recently adopted in compliance with the IMF’s dictates, allowed the oil and gas lobby to impose constant price increases despite a general decrease of oil prices in the global market.

Moroccan King Mohammed VI stands on an oil rig, near the Algerian border, during a visit to the Talsint region (AFP)

Moroccan King Mohammed VI stands on an oil rig, near the Algerian border, during a visit to the Talsint region (AFP)

It is noteworthy that, after the liberalisation of fuel prices and the closure of La Samir Refinery, companies including Afriquia, which controls at least 19 percent of the market and is owned by the Moroccan conglomerate Akwa Group - majority owned by Aziz Akhannouch, the long-standing minister of agriculture and fisheries - amassed significant profits. With the end of production at La Samir, these companies imported more refined petroleum products to sell on the domestic market.

Forbes has estimated Akhannouch's net worth at $1.6bn. In 2016, he was ranked in the 28th position on Forbes's annual list of the world's wealthiest Arabs. He played a central role in the five-month deadlock around forming a new government in late 2016 and early 2017. Akhannouch is denounced by the ongoing demonstrators in northern Morocco who accuse him, as the minister in charge of fisheries, of being responsible for the death of Mohsin Fikri and have called for his dismissal. Until now, Akhannouch has not responded to these accusations publicly.

Accumulation by dispossession

Furthermore, Morocco’s ruling classes have benefitted directly from the adoption of policies that have resulted in the liberalisation of the public sector and the privatisation of state-owned telecommunication, steel and agricultural companies like Cosumar and Régie des Tabacs. Through these numerous privatisations, they have continued - or even amplified - the process of accumulation by dispossession initiated by colonisers before the fictitious independence.

Nowadays, according to Diana Davis of the Department of Geography and the Environment at the University of Texas, the majority of influential, rich families in Morocco have benefited from the giveaway of profitable state companies and cost-effective public services thanks mainly to their proximity to the centre of decision-making – in other words, the royal palace.

READ MORE►

COP22 in Morocco: Between greenwashing and environmental justice

Davis explains that neoliberalism “has been enthusiastically, if selectively, embraced by the Moroccan monarchy and much of the business elite in contrast to the opposition it has encountered elsewhere. This is due, in part, to the fact that the royal family and its patrons have benefited enormously from certain aspects of neoliberal restructuring such as privatisation.

“It is also due to some of the effects of neoliberalism which reinforce the government's political goals. It has recently been argued, for example, that many neoliberal reforms have acted to depoliticise the public sphere in Morocco and thereby delayed the democratic reform of an authoritarian regime.”

Ever-rising debt

The rulers in Morocco have consistently opted to take the country into debt to compensate for their misguided choices, leaving the country’s public debt today at the record-high level of nearly $100bn.

Most Moroccans, particularly the impoverished, will have never set a foot in an ordinary train, let alone a high-speed one, but they have to pay for it

The debt policy, in turn, has had a catastrophic impact on Morocco, not only by absorbing over one-third of the state budget to pay for debt services, but also by maintaining our dependency to international financial institutions, Western governments and corporations through loan conditions.

It doesn’t stop there. Lenders also impose their preferences on projects with the knowledge of the ruling elites. The French high-speed train (TGV) project between Casablanca and Tangier is a good example of this. The initial studies of the project were carried out by a French consultancy firm and sponsored by the French Development Agency (AFD) along with French and Gulf banks. Two French companies, Alstom and Railway, have been the biggest beneficiaries of the project.

A carriage of a high speed train TGV produced by Alstom is loaded on a ship leaving for Tanger, at La Rochelle's harbour in France in June 2015 (AFP)

A carriage of a high speed train TGV produced by Alstom is loaded on a ship leaving for Tanger, at La Rochelle's harbour in France in June 2015 (AFP)

Most Moroccans, particularly the impoverished, who will have never set foot in an ordinary train, let alone a high-speed one, find themselves obliged to pay debt services including interest at the expense of essential social sectors such as health and education.

The crushing machine of climate change

Morocco is an example of climate injustice which characterises so many parts of the world nowadays. Indeed, Morocco is one of the least polluting countries worldwide (less than 1.7 tons of CO2 per capita per year) and its responsibility for global climate change is insignificant. Nevertheless, Morocco is among the countries most affected by and the least prepared to cope with climate change impact.

The state’s retreat from the public sector and the regression of its resources as a result of the devastating machine of economic liberalism and privatisation have left the state unable to intervene to reduce the repercussions of those terrible changes, notably extreme events such as floods and drought.

A man walks through a dried out area that used to be part of the Tafilalet oasis, near Morocco's southeastern oasis town of Erfoud, north of Er-Rissani in the Sahara Desert (AFP)

A man walks through a dried out area that used to be part of the Tafilalet oasis, near Morocco's southeastern oasis town of Erfoud, north of Er-Rissani in the Sahara Desert (AFP)

Anthropogenic climate change (greenhouse gas emission resulting from human activities) and its dire impact on Morocco’s vital sectors, especially agriculture, are undeniable. Increases in temperatures and lower levels of rainfall as well as recurring droughts (1980, 1985, 1991, 2006, 2015 and 2016) and floods (Casablanca in 2010, Guelmim and Tiznit in 2014, Taroudant in 2016) are the main manifestations of climate change in Morocco.

A 2014 World Bank report predicts more catastrophic impacts on our region in the future if the highest polluting countries do not drastically reduce their emissions.

While Morocco’s ruling classes and elites acknowledge these changes and expectations, their economic choices and structural projects stand in stark contradiction with the action needed to tackle and cope with climate change. On the contrary, they are exacerbating its impact by multiplying the pressure on natural resources. Here are two examples.

In 2001, the king announced the Plan Azur, a government strategy aimed at attracting 10 million new visitors to Morocco by developing six new beach resorts. Given the global rise of sea levels and, consequently, the high risk of flooding at these new sites, the plan is problematic. In addition, there is a deep contradiction between the vast swimming pools and golf courses that the new resorts will house and the country’s dwindling water resources which have decreased by one-third since the 1960s. Experts have predicted that Morocco will experience absolute water scarcity, defined as 500 cubic metres per person annually, by 2025.

Farm labourers pick strawberries in the Kenitra province country side of Morocco (AFP)

Farm labourers pick strawberries in the Kenitra province country side of Morocco (AFP)

The second example is the Green Morocco Plan, a strategy which the Ministry of Agriculture and Fishing launched in 2008. As part of the plan, the country would promote the growing and exporting of “high added-valued” agricultural products like citrus, vegetables and fruits, which also happen to consume the most water.

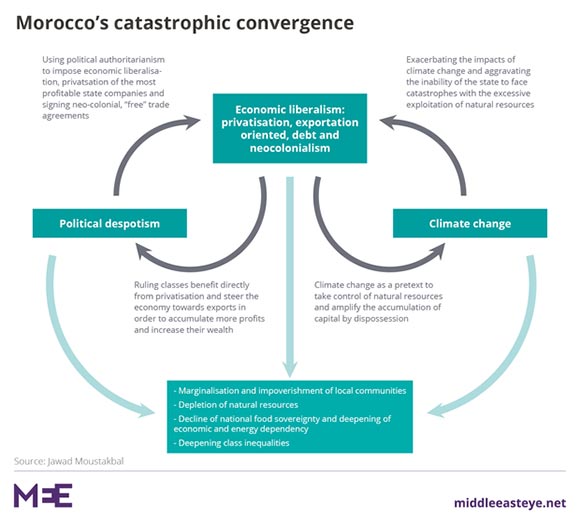

As such, these three factors, i.e. political despotism, economic liberalism and climate change, overlap and converge in deepening and speeding up the negative effects of one another. The following diagram is an attempt to summarise this process:

Elite 'environmentalism'

Last November in Marrakech at the UN Climate Change Conference (COP22), the country’s ruling elites held the green banner and green-washed their companies, luxurious cars and speeches in order to win their guests’ respect.

In the lead up to the conference, the government imposed new laws and decisions that purported to be environmental, but in fact only reflected an "elite environmentalism" in total opposition to the interests of the poor majority. These decisions have deepened the conviction of this crushed majority of people that the laws are enforced against them, exacerbating their suffering and humiliation.

In the lead up to COP22, the government imposed new laws and decisions that claimed to be environmental, but in fact only reflected an 'elite environmentalism' in total opposition to the interests of the poor majority

The most pertinent example was the zero-plastic bag campaign. This ban on the production and use of plastic bags, passed by the Moroccan parliament in October 2015 and which came into law last July, in fact, targets the type of plastic bags used by the poor while all forms of "first-class" plastic bags from big corporations were not banned.

Just days before the conference started and in a clear move to improve its image, the government also rushed through a decision to lift a ban on calls made through mobile internet connections on apps like Skype and Whats App. There had been protests on social media after the ban was imposed in January 2016.

These actions reveal how little regard the rulers have for citizens, their sole concern being how they look before their “masters” from “developed” countries such as France and the US. Their environmentalism is a top-down one which deems that the non-educated majority is responsible for all the ecological issues by throwing garbage in the streets and not maintaining the beauty of the public spaces.

Members of international delegations play with a giant air globe ball outside the COP22 climate conference in November 2016 in Marrakesh (AFP)

Members of international delegations play with a giant air globe ball outside the COP22 climate conference in November 2016 in Marrakesh (AFP)

Through this narrow framing of environmentalism, the government perceives the ecological crisis, either the global one linked to global warming or the local one linked to extractive activities, as an opportunity for enrichment and accumulation of additional profits. For that reason, instead of working on mitigation efforts, they focus more on energy production projects owing to their high profitability through public-private partnerships (PPPs), a euphemism for privatising profits and nationalising losses.

But it is the citizens who end up shouldering the responsibility of directly financing these energy production projects through hikes in electricity bills, or indirectly, through the draining of the state’s finances.

By contrast, private companies, including those owned by government officials and the ones of their French, Spanish, Emirati and Saudi “partners”, benefit from advantages and preferential terms stated in contracts tailor-made for them. Their environmentalism sees the ecological crisis as an opportunity to take control of what remains of our natural resources.

Elite ‘nationalism’

The ruling elites do not hesitate whenever the opportunity arises to flaunt their nationalism. Or use it as a pretext against anyone who exposes their oppression and exploitation by accusing them of being traitors to the nation and serving a foreign agenda.

Rather than listen to their demands and grievances, Minister of Interior Abdelouafi Laftit, for instance, has accused the protesters and activists in the Rif of being separatists and threatening the country’s territorial integrity.

They do not hesitate to flaunt their patriotism even if they deposit most of their money in banks in Switzerland, France, the US and other tax havens, as the Panama Papers have revealed. They flaunt patriotism even if they own property and secondary residences in Europe and US.

Furthermore, some of them consider their house abroad as their main residence while their home in Morocco is considered as secondary, one to be kept as long as it allows them to accumulate profits. They do not hesitate to show their Western passports in order to escape from the bureaucratic, racist and degrading rules imposed by “rich” countries on Moroccans to get a visa.

Their nationalism is superficial and sporadic, embodied, for example, in gathering poor people and taking them to the capital in buses for marches whose objectives they ignore such as those organised against Ban Ki Moon or the Spanish Popular Party following its declarations about the conflict over Western Sahara, then welcome them and entertain them as if nothing had happened.

Their nationalism is in alliance with our old and new colonisers in their mission to "re-conquer" Africa by appropriating its resources and controlling vital sectors like banking and energy, exactly as they did with our resources and vital sectors in the name of its “Moroccanisation”.

A path of hope

In her book This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs the Climate, Naomi Klein argues that the current catastrophic environmental crisis resulting from the globalised capitalist model of production, distribution and consumption is an opportunity to change everything.

We must break with the solutions from the past, conceived elsewhere and parachuted to our reality in an absurd way

In fact, this model threatens life on earth as we have known it until now. And it is for this reason that this ecological crisis provides a golden moment for the emancipation and disposal of all forms of injustice and social disparities – and I adopt this motivational and hopeful view for Morocco. Radical change nowadays is not an option but a necessity owed to the majority of our people as well as to our future generations.

Any serious alternative societal project in Morocco cannot fail to consider the three crushing machines of political despotism, economic liberalism and climate change and their catastrophic convergence. Our alternatives ought to take into consideration our concrete reality, start from our own culture and traditions and become reconciled with our identity.

We must break with the solutions from the past, conceived elsewhere and parachuted to our reality in an absurd way. We have to break with the myth of modernity and the Orientalist view of development’s possibilities in our countries. The models for their societies were not replicable and they have failed our society.

We have to overstep our old and new colonisers so that those lagging behind will become the first ones, as Frantz Fanon wrote. We have to establish, in the heart of our alternatives, the complete sovereignty of local communities over their resources, including land, water, sun and minerals, which they could democratically, altruistically and complementarily manage from themselves and others.

Along with resources, we must build a better Moroccan in which citizens also have control over their institutions so that they respond to the essential food, education and health needs of the majority in a way that respects ecosystems and their renewing capabilities.

- Jawad Moustakbal is a member of grassroots activist alliance ATTAC/CADTM in Morocco.